The Whiskey Wars

and

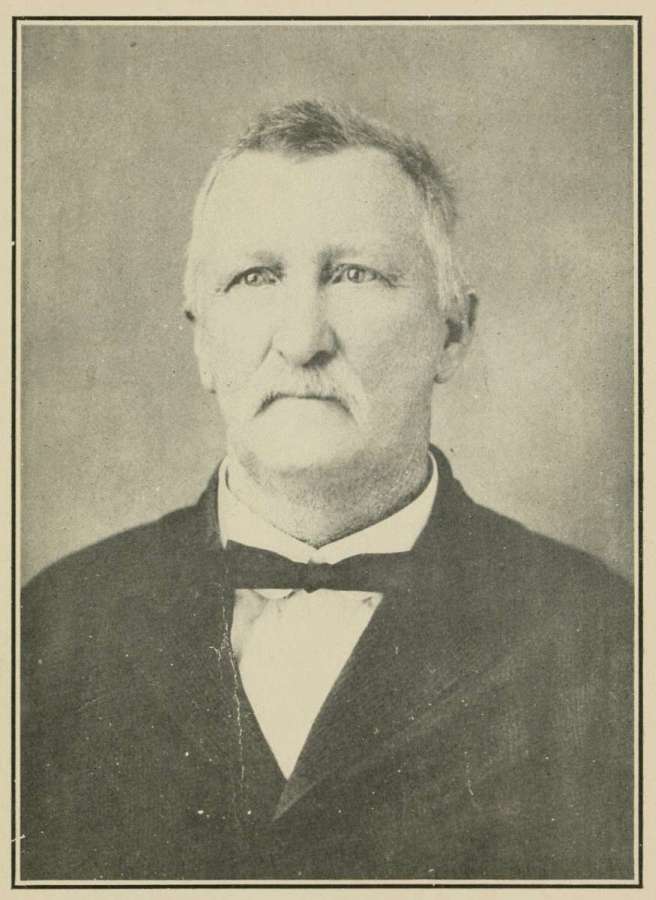

Colonel Frank Maner Mixson

Frank Maner Mixson

Photo from his book

Reminescences Of A Private

In 1894 civil disobedience broke in the state of South Carolina between the whiskey and anti-whiskey groups within the state over the Dispensary Law enacted to control the sale and distribution of liquor. South Carolina being known for some of the best whiskey at the time, the conflict became known as the Whiskey Rebellion or Whiskey War.

Prior to 1890, the control of the government of the State was in the hands of the remnants of the old slave-holding aristocracy, which ruled as much as possible as was prevalent before the Civil War. In 1892 a new democratic governor was elected in part with the promise to lead the fight “to free the State from the rule of these old Bourbons” and by appealing to the negroes for votes. The Bourbons at the time were some of the best-trained intellects of the state and had control of the press and the banks and opposed every act the democratic administration.

In 1892 the state passed the Dispensary Act as a compromise between the wishes of the ultra-prohibitionists and the whiskey people intending to get rid of the worst features of the liquor traffic, while permitting it to those who desire to drink it in moderation. The new law banned the private sale of alcohol setting up a system of state-controlled dispensaries. This new control did not sit well with the Bourbons who had profited from the sale of liquor they control. The Bourbons not wanting to loose their source of income, begin to sell liquor outside the state control in hidden hideaways called “blind tigers”. The state constables were always looking to close down the blind tigers for they cut into the state dispensary profits. This battle between the constables and the blind tigers was widespread with people supporting both sides. Rev. T.G. Herbert in a letter to the editor of the Edgefield Advertiser wrote, “I think the right way to regulate a tiger (whether he be blind or with two dangerous eyes) is to take his tail off just behind his ears.”

The distribution of the revenue from the state dispensary was controlled by Gov. Tillman who used it to bring the cities into line. In January 1894 the governor sent a letter to all the city mayors and towns of the state calling attention to the dispensary law, which provides that unless the police of the municipalities enforce the law against blind tigers the municipalities would be deprived of their share of the revenue derived from State barrooms. This did not set well with the governor of Charleston who replied, “Our self-respect compels us to state that the inquire made in your communication is not only without precedence, but that it is objectionable in that it implies an action of doubt as to our loyalty to the laws of the state which we are sworn to obey”. And the Sumpter Watchman said, “Surely there are no blind tigers in a town that has an ordinance against selling liquor. We had been told that if this city would only pass an ordinance against the sale of whiskey, that the constables would have nothing to do.” But the constables found “blind tigers” arresting the colored fruit dealer who ran a little shop on Main Street next door to Levi Brothers for selling liquor in violation of the city ordinance. (Jan. 17, 18943)

During the year of 1893 the newspapers were filled with discussion on the benefits and drawbacks of the Dispensary Act. The prohibitionists said it wasn’t enough, others said it was a good compromise for it shut down a lot of the blind tigers while the Bourbons said it went too far. The state promoted the liquor at the dispensaries was “pure” while the blind tigers sold the meanest whiskey.

In April of 1893 Col. Mixson was at the Governor’s mansion in Columbia for the annual inspection of the Governor’s Guards when he had an encounter with Captain Bateman of the guards. It that when Col. Mixson went to do the inspection, Capt. Bateman refused to be inspection stating that he didn’t’ know by what authority Col. Mixson wanted to inspect them . Col. Mixson explained that Col. John Gary Watts had issued the direct order that Col. Mixson should do the inspection. It was reported that Capt. Bateman would be court martialed for the infraction.

In February of 1894, Col. F.M. Mixson told newspaper men that “there has been no diminution in the Reform ranks of Barnwell County, which he said is the banner Reform county of the State. The Colonel then went on to say, “While the Dispensary had caused a few people to leave the ranks many more Conservatives have become Tillmanites because of the law. There are many more Reformers who want to see Governor Tillman put back in the office for a third term and if he wants the place again he can get it without turning his fingers. These Reformers feel that the Governor’s strong hand will be needed in this State for several years to come. This is the feeling. It is a spontaneous one, and the Reformers hate to see the Governor release the reigns of his office.? (Feb. 14, 18944)

In March of 1894 the situation takes and interesting turn when the state sold a lot of whiskey which had been seized by revenue officers and was being held in the Federal building. Col. F.M. Mixson was present at the sake and bought most of the whiskey for the State Dispensary paying $1.15 a gallon for it. Before the Colonel paid for the whiskey, a warrant was put out for its seizure and for the arrest of the men who bought it. When officers went to seize the whiskey, they found it still there and not paid for. Apparently, the Colonel got wind of the plan and didn’t pay for it. (March 21, 18945)

The new law gave constables, when armed with proper warrants from the civil authorities, the right to search private residences for the seizure of contraband liquors in order to prevent men turning their private residences into “blind tigers,” were they could sell liquor with impunity. This provision stirred up anger against the government using the assertion that their liberty was in danger. This stirred up bitter, unreasoning passion in the cities and towns against the constables, and threats were freely made against them. Being in danger of bodily harm, after having been mobbed and pelted with rotten eggs on more than one occasion, the constables were armed for their own protection

The governor accused the newspapers, controlled by the Bourbons, of sowing seeds of discord against the governor and the democrats. It came to a head in April 1894 when people in towns of Darlington, Florence, and Sumter banded together for opposition to the Dispensary Law and especially the constable feature of it. Large numbers of armed men gathered on the streets for the protection of a "liberty" which was not in danger. The five or six constables in Darlington were followed by this armed mob which guyed, cursed, and abused them. The governor sent a military company from Sumter to Darlington for their protection of the constables. The next day the town bell was run to call the conspirators who turned out heavily armed chasing the constables out of town. The conspirators took possession of the three towns, committing many acts of violence with dead on both sides.

In some cases, the local authorities sided with the conspirators and were reminded by the governor that part of the profits from the Dispensary Law goes to the towns and that these funds would be withheld if they did not enforce the law. In Florence this incited the mob even more who then looted the Dispensary there. The governor then ordered militia companies in the towns to quell the unrest. In Columbia, the old political Bourbons, aided by the whiskey element, brought such pressure to bear upon the companies that they refused to obey the orders of their Commander-in-Chief. In Charleston thirteen and the entire fourth brigade refuse to turn out. In addition, armories in some towns were broken into and their guns stolen. The mob also seized the telegraph lines and the railroad stations sending out “many blood-curdling and sensational dispatches.” before the governor ordered the railroads to shut down the telegraph system until they could be retaken. This of course force caused considerable dissatisfaction among the newspapers.

It all came to a head on the steps of the governor’s mansion when the governor made a speech that did not go over well with the attend militia guards who threw down their helmets and guns and marched off. The governor then gave orders to the captain of the militia. The militia men turned to the caption saying they would obey whatever decision he made and the Captain then informed the governor he would consult with his remaining men and announce their decision. After met and unanimously decided to follow the action taken by those who left, and the company declared themselves disbanded and the Governor was so notified.

Finally, companies of the militia that supported the governor arrived in the capital of Columbia in such numbers to overawe the mob. Many farmer volunteers also arrived to support the governor, “taking their horses from the plough, and, shouldering their shotguns, hastened to sustain the government of their choice.” Colonel Frank Manor Mixson, retired, was commissioned and placed in command of the forces in Columbia.

The Governor issued orders to the captains of the armories that were looted to have the stolen guns returned. The captains said it was impossible for them to do so as they did not take them and did not know who did. When it became know to the people what the captains said, most prominent citizens, in the interest of peace and order, and to prevent the Governor from taking extreme measures, encouraged the citizens to return the arms which they did.

Within a few days the uprising was over and the governor put out the following statement:

"The Dispensary law was enacted by the Legislature, by the majority of the representatives of the people. It is the law until the Supreme Court declares it unconstitutional or until repealed.”

R. R. Tillman

Shortly after the uprising in the South Carolina Supreme Court declared the act of creating the dispensary system in violation of the state constitution and Tillman closed the dispensaries. Coming to the end of his term as governor, Tillman in his ran for the Senate which he won supported by Col. F. M. Mixson. John Evans, who was supported by both Tillman and Mixson was elected as the new governor. This had the immediate effect that the then State Liquor Commissioner that was appointed by Gov. Tillman resigned and the new Governor Evans appointed F.M. Mixson as the new Commissioner.

Wasting no time, in January 1895, Governor Evans gave orders to have all dispensaries re-opened throughout the state despite the court injunction closing them. He went further and instructed all constables to cease looking for “blind tigers” and to focus on looking into the importation of liquors into the state. (Jan 16, 18953) Although this sat well with the operators of the blind tigers, it caused a whole new area of contention.

As the new Liquor Commissioner, Col F.M. Mixson ordered the opening of twenty-five new dispensaries as an “effectual weapon against the blind tigers” and as “as save way of increasing the profits of the system.” Chief Constable Fain said, “the blind fellows have been killed out, he was satisfied that they are helping to kill themselves out in the most effectual manner by selling stuff that is not fit to drink. This was his experience at least.” (Jan. 30, 18956)

In March of 1895, Col F.M Mixon ordered 400 cases of gin from Ulsman, Goldsborough & Co. so that South Carolinian’s can make Manhattan cocktails. Mr. Mixson said, “The introduction of the cocktail is purely and experiment but one that doubtless prove popular.” (March 13 18956) An editorial in the Watchman and Southron said about this, “The last vestige of the claim that the dispensary is a temperance measure has been knocked into a coked hat by the cocktail scheme of Dispenser Mixson. Crack ice next.? Commissioner Mixson set the for pure alcohol to druggist and general consumers at $3.50 per gallon, but if they brought their own container and buy not less that five gallons they could get it at $2.50 per gallon. Bourbon price set at $2.50 per gallon. But there was some disruption when in April “Quite a sensation was created here yesterday when a barrel of corn whiskey, tree parts full, was discovered a few steps from a public street in an open place. It bears Commissioner Mixson’s name and was probably stolen from a car in route to Columbia.” (Apr. 3, 18956)

A major contention point for the new dispensary laws came from those outside the state of South Carolina saying laws violated interstate commerce laws and in late April an injunction was ordered by a federal judge against South Carolina to be “enjoined and restrained until further order of this court from interfering in any manner whatsoever with the commerce between the State. (Apr. 24, 18956) Another lawsuit was filed by West Virginia against South Carolina for seizing liquor brought into the state in violation of the SC state law and that the provisions of the dispensary law are in violation of the United States interstate commerce law which “practically destroys the effect of the dispensary law. (May 3, 19857) The railroads were caught in the middle with them transporting the liquor from into South Carolina.

Governor Evans declared his intent to disregard the injunction and in May Commissioner Mixson issues an order to constables commanding them “to be particularly vigilant in the detecting and seizing liquors.” (Apr. 27, 19858) In May, Col. Mixson was ruled for contempt of court for the disobedience of the order of the injunction to stop seizers. When Col. Mixson was brought to court for the contempt, Mixson backed down from the position taken by the Governor Evans and disclaimed any intentions to disobey or treat the order of the court with contempt. While the court was in session a brass band in the street outside played “Where is My Wandering Boy To-Night?” The Judge was skeptical about Mixson’s defense asking, “Then I understand you to say that he (Mixson) did not mean that as on order to seize liquors?” and the defense responds, “He swears to that your honor.” (May 8, 18953) The next day, after deliberation, Judge Goff dismissed the case. The opponents of the dispensary system naturally were highly elated, and the wires were kept hot to-day ordering liquor from Augusta and other points outside the State. (May 9, 18959) Although the contempt case was dismissed, Judge Goff declared the liquor registration law unconstitutional and issued an order restraining Supervisor Green from performing the duties of his office.

That did not stop Liquor Commissioner Mixson who continued seizing liquor coming into the state and in June he was arrested for seizure of two barrels of beer shipped from August to a company in South Carolina. At the court hearing, Mixson expressed a willingness to return the seized beer as he was satisfied it was for personal use. Commissioner Mixson was fined $1000 and released under their own recognizances. (June 6, 18959) But this again didn’t deter Commissioner Mixson who were again hauled into to court for the seizure of beer while in the hands of the Southern Railroad Company where it arrived from Augusta Georgia. Mr. Beck who ordered the been said that it was for his own use and thus should not have been seized. The judge ordered the package to be found at the dispensary and brought to the court and for Frank M. Mixson to be arrested. Seizing liquor from the railroad was a particular touchy area with the Federal government because the South Carolina Railroad was in federal receivership at the time and thus, they were effectively seizing from the federal government. After appearing in court, Mr. Mixson agreed to turn over the seized liquor to the US Marshal and he was released under a $500 bond. (June 12, 18953)

At the end of June Commissioner Mixson reported record income from the dispensers instructing them to extend their hours to “allow the early bird to get his flask as well as to let the State get in a little more money.” The new hours would be from 5 AM to 7 PM. (June 20, 189510) The Legislative committed in charge of examination into the management of the State Dispensary concluded that the Dispensary under Col. Mixson’s supervision “to have been managed in a thoroughly business-like manner” and the Col. Mixson should feel proud of his report. The Manning Times reported published the full report under the byline “Mixson’s Monopoly” (June 26, 18953) The report did bring to attention that the Dispensary had yet reimburse the State for the initial $50,000 provide to it under Gov. Tillman in 1893. The News and Herald in Winnsboro under the byline “Will the Mix Up Mixson” wrote that it could not learn the state of the proceedings against Colonel Mixson was for the marshal would not give any information, but it is more than probable that these people will have to spend a time in jail. “So it all comes out even. The Unites States jails South Carolina constables and South Carolina jails violator’s of her Dispensary law.” (June, 27, 18953)

In spite of all ruckus going on, State Liquor Commissioner Mixson report record income from the sale of liquor and in August Commissioner Mixson place in the hands of the State Treasurer a check for $50,000, thereby returning to the state the whole appropriate made to start the “state gin mill” in operation. (August 21, 18954) Also in August Commissioner Mixson stated it “impossible to keep up with the demand for State grog.” And recommend changes that would bring $200,000 more income to the State.

In August Commissioner Mixson was brought to court for the case from the past May in which liquor that Mr. N. G. Gonzales had ordered was seized which Mr. Gonzales claimed was for personal use. The judge ruled that F.M. Mixson (and others) do show cause before this Court on the 4th day of September, 1895 why the said liquor so seized should not be delivered to said petitioner as prayed for, and why they should not be attached for contempt in violating the order of this court. (Sept. 4, 18953) Col. Mixson and the others charged presented their side on the case as scheduled on September 4th where after the review, the judge felt he was unable to proceed and referred the matter to a special referee to looking into it. (Sept. 11, 19853)

In December Commissioner Mixson was again brought to court for the case from the previous August in which liquor was seized from a private club. The judge orders Commissioner Mixson to return to the members of the club the liquor seized and the constables Speed, Davis and Lafar who did the seizing to be taken into custody until they have paid the entire costs of the proceedings. The papers were served immediately. (Dec. 4, 18956) A few days later Judge Simonton dismissed the Contempt case against Commissioner Mixson (after the seized beer was returned to the owner). (Dec. 13, 189511)

In July of 1896 Governor Evans and commissioner Mixson got into hot water being charged with canceling dispensaries’ insurance and giving the contact to his brother. Commissioner Mixson then produced a letter stating that in 1895 that he alone was responsible for all insurances place on dispensaries; that the Governor Evans knew nothing about it and the letter was written without the Governor’s knowledge. The Judge Earle then asked Evans “Don’t you countersign all checks and didn’t you know that it (the insurance) was at a higher rate?” Governor Evans respond that he has signed thousands of checks never knowing what they were for. After a heated exchange of words between the Judge and the Governor, Evans made a speech for which he was “loudly applauded and a handsome basket of flowers was presented, where upon he said that the ladies were with them and that “he had go the coon and gone on.” Which bought cheers from the spectators. (July 29, 189612)

Also, in July a charge was by Mr. Duncan that Governor Evans had told him that his predecessor, Gov. Tillman, had filled his pockets with rebates. It also was stated that Commissioner Mixson had been offered $562.50 per carload in rebates by the representatives of the Mill Creek Distilling Company. Gov. Evans knew of this and ordered Colonel Mixson to purchase the whiskey, but that Col. Mixson refused to make the purchase and that Gov. Evans told Col. Mixson that “Tillman had filled his pockets from this source.” The liquor was ordered, and the rebates were---where do you suppose? The fact that the rebates were made was not an issue, the issue being that if the State received the rebates then Commissioner Mixson’s books should show the fact. Since they did not, then “somebody made way with the money—stole it in other words.” (July 29, 18963) Over the next few weeks the story spread and was reported on in various details in the Anderson Intelligencer, The Union Times, The People’s Journal, The Manning Times and others with many calling for Col. Mixson to come forth and clarify what happened but Col. Mixson remained silent.

The situation became more complicated at the end of August when, as reported by The Abbeville Press and Banner, “Evidence of Tall and Premediated Lying, Commissioner Mixson and his nephew flatly contradict.” Robert M. Mixson, a nephew of Colonel F. M. Mixson, was a soliciting freight agent for the Louisville and Nashville railroad company. According to Col. Mixson, Robert Mixson requested Col. Mixson write him a letter of introduction to several parties in the interest of his railroad which Col. Mixson did so. Col. Mixson said the letter was only for introduction and did not authorize Robert to make any proposition from the Col. According to Robert Mixson the letter read: “This will be handed you by my nephew, Mr. R. M. Mixson, who represents the Louisville and Nashville railroad. Anything you can do for him will be appreciated by your respectfully, F. M. Mixson.” Robert said he secured the letter for the reason that he was anxious to hall the shipments for the Mill Creek Distilling company. Robert went on to say that he met with the Mr. Hubble from the distillery who offered him 50 cents per barrel on whiskey he would sell to the state dispensary which he refused. Hr. Hubble in the following month increased this offer to $1.00 a barrel. (Aug. 26, 189612)

Mr. Hubble, the Mill Creek Distilling company secretary, responded with a letter published in several newspapers saying, “The reason this man Mixson is so bitter against me is because I would not employ his agent and pay him a commission. This agent said he could get me the business of the State dispensary and wanted a commission of $1 a barrel.” He went on to say that his company furnished the capital to make the dispensary a success and the dispensary owed Mill Creek more than $92,000 at one time and the books of the dispensary would prove it and “the management of the dispensary would be cold-blooded and ungrateful if they did not give us a portion of their business without our having to ‘put up’ for it.

The scandal continued into September, with articles in most all the state newspapers and even some as far away as the Salt Lake Herald in Utah, The Record-Union in Sacramento, California. The Morning Times in Washington, DC reported on September 7th that that Commissioner Mixson and his son made statements with the latter “acknowledges that he collected for his brother $740.50 in whisky rebates from the Live Oak Distilling Company, but his father knew nothing of it.” Col. Mixson’s son is Robert T. Mixson. Col. Mixson stated, “Whilst my boy did get some money from Live Oak people, I never got a cent of it and know nothing of it until the money had all been squandered, and I never received a cent since I been in the Sate Dispensary other than my salary.” He then turns on Governor Evans saying, “Now, since Governor Evans accuses me so lavishly of getting the public money, will he tell us how he ran up his expense account against the dispensary.” for the amount of $150, approved it himself and received it as shown in the dispensary records. Newspapers in Kansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Virginia, Ohio, Montana, Indiana reported the story.

In the fall it came clear that all the commotion was about a race between Evans and Earle for the US Senate with both sides dragging up dirt on each other. The Abbeville Press summed it up in the subtitles: Tillman Accepted Rebates; Mixson’s Sons Accepted Presents; The Price of Liquor, Mill Creek Distilling Company; Mixson’s son is said to have received thousands of dollars from whiskey people; Innocent Father—Guilty Son; The Son’s Sorrow for the Disgrace Brought upon his Father; New Board Removed from Temptation; The Desire of Governor Evans to Purify the Board the Probable Foundation for this War on Him; Tillman and Evans are Faithful Friends; Governor Evans has Inquired Today. The article was followed by “Tillman Talks” a letter from Tillman who was then a senator and then a letter “Here is the Truth” by Judge Earle. (Sept. 9, 189612) In the following weeks more articles with letters from all parties appear with titles “Letting the Light in, What Gov. Evans has to say” and “Letting More Light In, Commissioner Mixson replies”.

The South Carolina Board of Control begin an investigation on September 17. Governor Evans, the first witness said he new beyond hearsay evidence was that W. T. Mixson, a son of Commissioner Mixson, had gotten $2,698 from the Live Oak Distillery Company, that he had no evidence against the commissioner and that he himself denied most positively that he had ever received any commission or that any had been offered him. Clerk Scruggs of the board of control testified that he had been told by the manger Yost of the Live Oak company that Commissioner Mixson was being paid commissions and had showed Scruggs where he had paid Mixson’s sons $3,600 in two months. (Sept 17, 189613)

Startling Disclosures

Governor Evans responded in another letter to the press that Mixson had received no rebates but he knew that Ben Tillman had lined his pockets. Evans went on to say that it was reported to him that Mixson had received a desk and his two sons were accepting presents from whisky dealers in the shape of diamond pins, gold-headed canes, etc. and that he warned Mixson about the danger of such gifts and “impressed upon him the importance of keeping aloof from such influences and also in keeping his boys from temptation.” Mr. Scruggs told Gov. Evans that he could provide evidence to convict the men if the Evans would allow him to leave the State. When the Governor learned of J.W. Mixson going to Cincinnati and was being entertained by the whiskey dealers, he told R.T. that if he did not cease he would be convicted by the public of getting rebates whether true or not. Upon his return from Cincinnati, J.W. called upon the Governor and explaining his conduct stating, “he had gone on a business trip, something about bicycles.” But the Governor learned that J.W. “was not the bicycle boy, but the stenographer of the Sixth Circuit.” (Note: Col. Mixson’s son W.T. Mixson was a well-known bicyclist winning many races and having a bicycle store in Columbia which made bikes) Governor Evans said that he could only remove the Commissioner Mixson for cause and that if Mixson could prove his innocence that he could not remove him. Mixson then called upon the Governor, producing a letter from his son in which his son confessed and deplored the fact that he had brought disgrace upon his father and family, and had left home never to return. The Governor was moved with sympathy for them and told Mixson “to see the boy and not let him run away.”

Commissioner Mixson replies in a letter to the public that his son J.W. told him that Gov. Evans brother and W.T. were talking about going into a deal to make something off whiskey sales. Mixson told his son that he “could not afford to have anything to do with such a deal: It would be ruinous and that he (Commissioner Mixson) would not buy from any house that they made arrangements with.” Mixson went on to say just after he took office, Governor Evan told him in unmistakable language: “Don’t buy from Mill Creek.” Mixson went on to say that Tillman got rebates from them, “and it must be so, else how could Tillman meet the expenses with one daughter in Virginia at school, a son at Clemson and living as he does.” To Tillman who said “Mixson has never had the manliness to either affirm or deny.” Mixson responds with “” must ask the Senator (Tillman) if he or Governor Evans either had the manliness to ask of me a confirmation or denial.” About the matter of his son in Cincinnati Mixson said his two boys entered into a copartnership under the firm name of J.W. Mixon & Co., bicycles, and the latter part of that month his son J.W went to Cincinnati to keep an appointment with a bicycle manufacturing firm. It was only after his son returned that he learned of his son taking rebates while in Cincinnati and when he asked his son about the matter and he acknowledge it was true. The boy, seeing how badly he had hurt his father, wrote the letter he presented to the Governor. Mixson then says he never got a cent of the money his son received, and he had never received any rebates other than his salary (Sept. 18, 189611)

After the news broke, in September his son J.W. Mixson, who was the stenographer of the circuit court tending to Jude Buchannan, resigned from the position. In J.W.’s letter to Judge Buchanan his says, “unfortunately for me, my name has been connected with the dispensary matter now under investigation, and while I have done no wrong, and consequently am guilty of no crime, I wish to relieve you entirely of any and all possible embarrassment that might arise by my continuing to hold my position.” He goes on to say that he collected the money on behalf of his brother J.T. Mixson who upon delivering it, he told warned his brother “against receiving commission money, as it might in some way implicate our father.” He goes on to say that whether it is business people approve of or not, it is lawful and many respectable engage in it and his brother is guilty of no crime. (September 30, 18963)

In an open letter in the Abbeville Press and Banner on October 14th, 1896 about the events:

“Can anyone in his senses doubt the fact that Duncan know all of a part of these different items which the Mixsons have admitted? With the brazen front of a Cataline, he (Duncan) reasoned that, at the late day Gov. Evans would not expose his old friend Mixson, and he reasoned craftily for Gov. Evans, like the Spartan you who concealed the fox in the bosom of his robe has, in trying to shield and old friend, met the same fate as that youth, who rather than betray the, to him, laudable secret suffered the beast to eat youth his heart and fell dead at the feed of the spectators.”

In October the State Board of Control investigation release a report on its findings. Saying, “The evidence that has been taken is, in the opinion of this board, insufficient to show that any officer or employee of the State dispensary has received rebates or commissions on sales to the dispensary, or to trace any money … or any such officer or employee has participated in such rebates or commissions.” The report did say letters from Mr. Yost, a manager at the Live Oak Distillery provide, shows that Mr. Yost had personal interactions with the two sons J.W. and W.T. Mixson. Mr. Yost says that he on several occasions in Cincinnati the saw J.W and J.T. “without any thought as to any possible construction that might be place upon it , and in entire innocence as to any improper suggestions he did consent to give a small brokerage commission to said two gentlemen.” Mr. Yost says in none of the interactions did the sons promise or assure him that they would solicit business from their father. As to why he paid the money he “thought that by having brokers in the field to assist in the creating a demand for the liquors or popularizing certain brand there would no injustice to the Sate of South Carolina, even if said brokers were related to the commissioner.” After all such business practices were a common, if not expected at that time.

Several of the letters from J.W. were printed in the paper. The first letter from J.W. to Mr. Yost he does say “I am also glad that your business relations will be what you desire. I think my father regards your firm as one of the best, and for that reason he will do what he can for you.” He then thanks Mr. Yost for “the token mentioned in the first paragraph of your letter”. An interesting aspect is that J.W. says to send any replies to his father care. His father undoubtedly examined every piece of mail that came to his house. The next letter from J.W. to Mr. Yost a few weeks later opens with the “package containing the ‘small token’ has been received. The next letter from W.T. to Mr. Yost says his father, Col. F. M. Mixson had received a lot of “Live Oak” pocketknives, but he didn’t get one and asks if Mr. Yost could send him about a half dozen. (Oct. 14, 189612)

Commissioner Resigns

On October 9, 1896 State Commissioner Mixson resigned his position and his duties would cease the next day. This was a completed surprise to everyone, even Col. Mixson’s friends. It was surprising because the investigation board had cleared him of all wrongdoing. Several members of the board were asked if they requested Commissioner Mixson to resign and they said they did not. In Mixson’s resignation letter he says he had wanted to resign for some months but “on account of the many rumors and slanderous reports in circulation I could not afford to do so, preferring to wait an investigation by your honorable board.” With the investigation completed, and exonerating Commissioner Mixson from any wrongdoing, he resigned. (Oct. 14, 189612) The next day when asked by the reporter for The Watchman and Southron about what he would do next, Colonel Mixson said he did not know but was sure of one thing and that was that he would make a living.

In November Governor Evans lost his bid for re-election and William Haselden Ellerbe was elected.

Even after Col. Mison resigned, the investigation continued and in July of 1897 it was found that part of official records of the State Commissioner’s office were unlawfully in the possession of ex-Commissioner Mixson and proceedings to recover them were to be taken at once. (July 7, 189712)

In August of 1897 Col. Mixson attended “The Great Confederate Reunion” Col. Mixson which was held in Greenville South Carolina. At the reunion, ”stirring scenes enacted in the sixties were vividly recalled.” It was well attended with groups of “these heroes” wearing grey could be seen at every corner, in the hotels and about in the public spaces. At the evening assembly, “a bevy of charming and picturesque women” marched into the building and received a standing ovation to receive “these promising young women of Carolina.” After the women were seated, the Sons of Veterans came in with less fanfare and took their seats on the front row. General Bonham spoke with much fervor in which he said “More than thirty years ago this people was declared conquered, and yet here are thousands who celebrate their part in this struggle.” Col. F.M. Mixson moved the adoption of the committee’s report. (Sept. 1, 189712)

Peculiar Accident

Col. Mixson faded from the news for several years then on November 14th 1901, Col. Mixson while attending the performance of “Don Caesar’s Revenge,” at the Columbia Theatre suffered a peculiar accident when between the third and fourth acts, an attendant in the gallery dropped his quite heavy walking stick to the seats below where Col. Mixson was seated with his wife and daughter. The stick fell straight down striking Col Mixson on the top of the head who then bent forward and hold his head where the ferrule of the cane had cut his head, making a painful flesh wound that bled profusely. Dr. Kendall, who was seated nearby, rushed to Col. Mixson’s side and he was at immediately taken to his house where Dr, Kendall dressed the wound. The doctor said afterwards that he considered the wound serious and had the stick been heaver it would have killed Col. Mixson. The police tool charge of the young man who dropped the stick. (Nov 21, 190114)

More Investigation

In 1905 the South Carolina set up another committee to investigate the Dispensary. At a meeting on August 23rd Col. Mixson was again called in and testified that, while he was Commissioner in 1895, he demanded 5 per cent rebates from every whisky concern from which he purchased liquor. The rebates amounted to $20,000 which he turned over to the State Treasurer. When asked about inducements offered to him for favoring certain companies, Col. Mixson said that several houses had offered him bribes, one a Mr. Lanahan from on distillery offered him $30,000. The Colonel said, “It was a strong temptation” and refused it and telling the man offering the bribe, “So help me God, I will never buy from you.” When Mr. Lanahan was asked about this made an unqualified denial of the charge and said, “I know Mixson. He made an effort to connect himself with our house, but we wouldn’t have him. This fact may account for his testimony.” Mixon then testified that Mr. Hubbell of Mill Creek Distilling Company offered him $262.50 in cash per carload of fifty barrels and that he promptly reported this to Governor Evans and he (Mixson) never bought a drop of liquor from the firm.

When asked about letters from the J.W. Kelley distillery, Mixson said he had the letters in the city but declined to give them up. The committee decided that Mixson must produce the letters or be imprisoned for contempt. Mixson asked for one day to produce the letters and the committed granted the request after Mixson promised not to destroy them or take them out of the city. (Aug 24, 190515,16)

The next day Mixson produced the letters, at first refusing to hand them over but his resolve weakened when an order was passed for him to have him placed in jail and he turned the letters over to the chairman. The letters from J.W. Kelley & Co., of Chattanooga, TN and were read in the morning session. After reading the letters said Representative L. Arthur Gatson, a member of the committee, showed that the whisky houses were “debauching the State and that there was corruption in high as well as low places.” Mr. Gatson went on to read extracts from the letters that were particular revealing. One letter complained of the “watered condition” of the whiskey. Another “Congratulations to the colonel on his winning ways.” And another about having whiskey shipped to them as mineral water. It also was found that the empty whiskey boxes were being sold back to the whiskey companies with the money going to individuals and not the state.

Other witness were brought forth with a Capt. R.E. Bakley, who was an assistant bookkeeper under Commissioner Mixson at the time, testified that he overheard a conversation between Mixson and Lanahan and that Mixson told Lanahan that he would have nothing to do with him in a business way because Lanahan company’s whiskey was flooding state’s tigers. Mr. Richardson, a revenue officer at the time, testified that a representative of one distillery told him “Well, I have formed and opinion of him (Mixson), he is either an honest man or a damn fool.” Explaining that “Mixson had refused an offer of $5 a barrel on goods brought from Cincinnati.” Richardson said when he reported this to Mixson the next day, Col Mixson confirmed the man made him the offer but he had “always stuck to make an honest living and didn’t propose to break over at this date.” The committee adjourned with the next meeting to be in September. (Aug 29, 190517)

In early September the newspapers were filled with letters and articles on the pro’s vs the con’s of the South Carolina dispensaries with a petition calling for an election on dispensary or no dispensary being circulated state wide. Senator Tillman, who created the dispensary when he was governor, vigorously defended his “child”. Four counties voted out of the dispensary system in September causing the state to lay off some of its constables. The committee resumed their investigation which revealed more details about acts of fraud, graft, corruption and stealing. In one case “extra bottles were found” in some cases which the dispenser either used for his own consumption, distributed to friends or gave them in payment for services around his home. In Union County, the judge ruled that the vote was legally held and ordered the dispensaries in the county closed. Other counties had voting scheduled over the next two months. It was expected dispensary advocates to take the case to the State Supreme court.

Part of the dispensary system was to provide funds to the school system from its profits which were supposed to be done by October 1st but come the second week of October, the dispensary had not turned over a cent for the use of the schools. (Oct 11, 19053). By the end of October, several more counties voted out the dispensary system with more making plans to do so.

On November 10th, 1905, The Union Times reported that the dispensary investigation had not been heard from it continued to go on. In November the people of Spartanburg County voted out the dispensary by a six to one majority while Florence Counted voted to keep the dispensary. On November 24th the case about dispensaries was sent to the Supreme Court which was expected to settle the case when they meet in December. On the 25th Anderson County voted to reject the dispensary.

On December 6th the Supreme Court ruled that the national government may property tax the liquor dispensaries of South Carolina. The Supreme Court also ruled that the dispensaries in two counties that people voted them closed, can remain open until the case is reviewed in January. (Jan. 16, 190618)

In January the Supreme Court rules unconstitutional the penalty clause of the dispensary Brice Act which penalized counties which voted out of the dispensary by stopping their share of the dispensary profits for schools. Also, the dispensaries kept open by the injunction must be closed. Senator Brice said, “I’m for wiping out the whole state machine and leave it to the people to settle by counties whether they shall have prohibition or high license under dispensary regulations.”

In the December 30th, 1910, The Union Times ran an advertisement for “Copies of Reminiscences of a Private, by Frank M. Mixson.” The graphic account of a F. M. Mixson’s experience as Confederate soldier’s war.

In January of 1911, the Confederate Infirmary Commission of Columbia elected F. M. Mixson as superintendent of the Confederate Home located there. The Manning Times, Feb 1, 1911. In August, F. M. Mixson “gave the veterans such an excellent account of the home—its present condition, it needs and its ambitions—that eh convention voted to have the address published in the leading papers of South Carolina.” (Aug. 30, 191119)

In November Col. F. Mixson unexpectedly dies.

Col. F. M. Mixson Dead

Well Known South Carolina Veteran

Dies Suddenly.

Columbia, Nov. 5—Col. F. M Mixson, head of the Old Soldier’s Home here, died suddenly this morning, heart failure being the cause of his death. He had risen apparently as well as ever, but at 10:30 o’clock suddenly passed away. The funeral services will be conducted tomorrow afternoon at his residence, at 4 o’clock, by the Rev. Charles E. Woodson, paster of the Church of the Good Shepherd, and the remains will be interred in Elmwood cemetery. Col Mixson is survived by his wife and the following children: Messrs. J. W., W. T. and J. C. Mixson, Mrs. W. A. Coleman and Mrs. Charles B. Sheer, of Montgomery, Ala.

Col Mixson was a native of Barnwell County and during his life held several public offices. He was assistant of Education under Mr. Mayfield; superintendent of the old Stat dispensary and the first dispensary commissioner under Governor Tillman. From the first of last January to the time of his death he was at the head of the Old Soldier’s Home in this city. Col. Mixson served in the confederate army as an orderly in Jenkin’s brigade. At the time of his death he was a member of Camp Hampton.

The Watchman and Southron, Nov 9, 1911

Further details from The Herald and News:

Col. Mixson was one of the best known veterans in the State. He was born in Barnwell County on December 5, 1846 and was the son of William J. Mixson. His father died when he was 6 years of age, and Col Mixson was adopted and reared by Col. J. J. Wilson of Barnwell County. He joined the Confederate army when he was only 14 years of age and served throughout the war in the First South Carolina regiment under Col James Hagood. He made fine record as a solider. Col. Mixson recently completed a book on the life of the private in the War Between the Sections, which made interesting reading.

F. M. Mixson part in the South Carolina Whisky Wars and the controversy surrounding it. Charges of him taking “rebates” and other gifts from the whiskey distributer and manufactures was never proven and he maintained his innocence to the grave.

References

- Our Whiskey Rebellion, North American Review, No. CCCCL, May 1894, by Hon. B.R. Tillman, Governor of South Carolina.

- The Whisky War, The Abbeville Press and Banner, Wednesday, April 4, 1894

- The Watchman and Southron, Sumpter, South Carolina

- The Manning Times, Manning, SC

- The Fairfield News and Herald, Winnsboro, SC

- The Anderson Intelligencer, Anderson, SC

- The Bolivar Bulletin, Bolivar, TN

- Birmingham Age-Herald, Birmingham, AL

- The Roanoke Times, Roanoke, VA

- The News and Herald, Winnsboro, SC

- The Union Times, Union, SC

- The Abbeville Press and Banner, Abbeville, SC

- The Copper County Evening News, Calumet, MI

- The Bamberg Herald, Bamberg, SC

- New-York Tribune

- The Daily Press, Newport News, VA

- The Herald and News, Newberry, SC

- The Yorkville Enquirer, Yorkville, SC

- The Laurens Advertiser, Laurens, SC